A Detailed History of Soccer

Soccer. The lovely game that hundreds of millions love, play…and call football.

Soccer. The lovely game that hundreds of millions love, play…and call football.

The pride and passion on display by loyal soccer enthusiasts and the animosity shown to their rivals put American sports fanatics to shame. Think Yankees-Red Sox is heated? Think the Red River Rivalry runs deep? Head to Spain, witness El Clasico, and then tell us what you think.

How did this love and passion for the game develop? From its humble origins to a grand spectacle like the 2018 FIFA World Cup, we will walk you through the history of soccer. Learn how a backyard game was popularized, organized, and then propelled to the world’s grandest stage.

Where Did Soccer Originate?

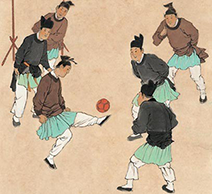

Everyone will try to convince you that soccer originated in their homeland. The Japanese ball-juggling game kemari is claimed to have been an early version of soccer. Likewise, the Chinese also claim to have begun soccer with their game Tsu’ Chu. In fact, FIFA has written that the earliest documented record of soccer is a description of Tsu’ Chu found in a 3rd/2nd-century BC military handbook.

Everyone will try to convince you that soccer originated in their homeland. The Japanese ball-juggling game kemari is claimed to have been an early version of soccer. Likewise, the Chinese also claim to have begun soccer with their game Tsu’ Chu. In fact, FIFA has written that the earliest documented record of soccer is a description of Tsu’ Chu found in a 3rd/2nd-century BC military handbook.

Tsu’ Chu was a goal-scoring game played with two teams attempting to kick the ball into either one of two goals in the middle of the field. Tsu’ Chu seems very similar to soccer, although there is little evidence to support any link between the development of the two sports. Others reason that Tsu’ Chu must have influenced modern soccer because the sports are so similar.

Elsewhere in the world, the Australians, Greeks, and even the Romans lay claims to the origin of soccer. A marble-carved representation of the Greek game episkyros leads to the game often being named the ancestor of modern soccer. The carving depicts a man balancing a ball on his knee in soccer-like fashion. Other historical discoveries are unable to find any record of a soccer-like game in ancient Greece, leading many to believe episkyros was simply a ball-juggling game.

Britain is often regarded as soccer’s true land of origin because this is where the sport was first formally organized. Nowhere else in the world were records of games found as similar to soccer as the ones in England and Scotland.

As the FIFA website explains, modern soccer, rugby, and American football all share their origins in medieval English variations of the game. The earliest discovered mention of a verified soccer-like game comes from a Scottish text entitled Vocabula, dating back to 1636.

A very fun yet chaotic example of a soccer-like game in medieval England was mob football. This sport was played between two very large teams, often containing hundreds of members each. Each team would be attempting to get the ball across the opponent’s boundary line. The catch was that this game was often played across an entire town or between neighboring towns. This made for playing fields that spanned several miles with no set boundaries.

The Game Becomes Organized

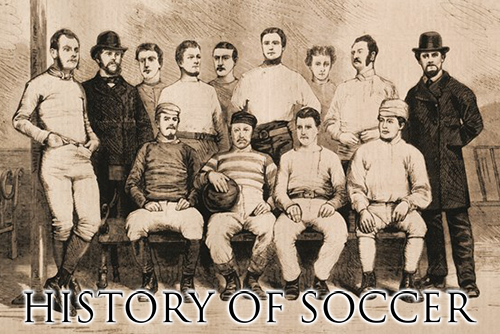

All sorts of different variations of soccer were becoming popular across western Europe throughout the 19th century. Cambridge University published rules in 1848 in an effort to standardize the sport, but these rules did not catch on. It was not until fifteen years later that the Football Association in London was established to create official rules and disseminate them wherever soccer was being played.

It was during this time that the first club teams and tournaments were organized. In the 1870s, a crossbar was added to the top of the goal, and 90 minutes became the standard time for a match. This time limit has not changed since it was decided upon over 140 years ago.

This early form of the game did not contain goal kicks, corner kicks, or penalties. A more encompassing governing body, the International Football Association Board (IFAB), was founded in 1886 and began implementing some of the modern rules we associate with soccer.

Soccer was originally considered a gentleman’s sport and contained no referees. All disputes were settled by the team captains in a civil manner. Umpires were soon hired to settle any conflicts. In 1891, a head referee was appointed to oversee all calls and was given the authority to call penalties and issue red cards.

Late nineteenth-century soccer was becoming quite uniform and increasingly popular throughout Britain and all of western Europe. International teams were common by this point, with England and Scotland playing the first recognized international soccer match in 1872, drawing 0-0.

Even by this time, match rules were sometimes determined right before kickoff. Impressed by London’s efforts to standardize the game and the progress by IFAB, the Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) was created in 1904. FIFA mandated that a footballer could not play simultaneously for two different national teams, while also gaining the power to suspend players for various violations and enforce their official rules on international matches.

The first official international match under FIFA regulation took place in May of 1904, featuring Belgium and France. Already at this time, talks of organizing an international soccer competition – like the World Cup – had begun. One major hindrance was that IFAB and FIFA did not agree on all of the game’s rules.

FIFA’s original seven member nations were Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. The British-run IFAB was initially resistant to control by FIFA. In 1913, the British relented, FIFA joined IFAB, and soccer became united throughout Europe under one set of rules.

Making Soccer More Exciting

Soccer rules underwent many more changes in the early twentieth century that were aimed at increasing scoring. Relaxed offsides rules made passing downfield much easier and eliminated the need for excess dribbling. In 1925, goalkeepers were restricted to using their hands only when in the box. FIFA knew their fans loved to see goals, and these changes allowed for many more scoring opportunities.

With the increase in popularity of high-scoring sports such as basketball in the late twentieth century, FIFA felt the need to generate more goal-scoring opportunities. Offsides rules were once again modified in 1990, this time to their modern, attacking-friendly form.

In another major change, goalies were forbidden from picking up a backward pass with their hands in 1992. This made stalling exponentially more difficult. Vicious tackles from behind were then outlawed in 1998, becoming punishable by a red card. These two changes prompted more wide-open play and back-and-forth action.

To reduce controversy, FIFA began to take steps in the 2010s to eliminate the human element from officiating. They introduced goal-line technology in 2013, which determined electronically whether a ball had crossed the goal line or not.

The largest American football league, the NFL, implemented video replay review back in the 1999 season. It was not until eighteen years later, in 2017, that an extra official was assigned by FIFA to review plays and was given the power to overturn calls made by referees on the pitch.

The 2018 World Cup was the first of its kind to feature this technology, and the response was very positive. Fans appreciated how the chances of a match being decided by a blown call were dramatically reduced.

The Birth of Clubs, Leagues, and Tournaments

Another reason Britain is often attributed as the birthplace of modern soccer is that they birthed both the world’s first club team and the first league. Sheffield FC was founded in 1857, the first team of its kind. By 1888, the English Football League had been established, becoming the first national soccer league. This league still exists today. Its top division is named the Premier League, and it is considered very prestigious.

Around the turn of the century, soccer was no longer exclusively European. It was spreading quickly around the globe. North American national teams had begun playing matches throughout the 1880s. The New Zealand Soccer Association formed in the 1890s, along with South American soccer leagues in Argentina and Uruguay. This decade also saw rise to the first Asian football body, the Football Association of Singapore.

Shortly after FIFA was created in 1904, work began to organize world soccer competitions. The first Olympic soccer tournament was held in London in 1908, with Britain finishing first in the six-team field. The following year saw the world’s first official national tournament, the Sir Thomas Lipton Trophy, in Italy.

Early in the 1920s, African national teams began to play official international matches. With each inhabited continent now fielding teams, desire for a world-wide tournament intensified. Many of today’s most prestigious competitions, leagues, and teams debuted in the first couple decades of the twentieth century. The first Copa America was held in 1916. La Liga played its inaugural season in 1928.

The modern-day Spanish powerhouse FC Barcelona debuted in 1899. Their German counterpart, FC Bayern Munich, was founded one year later. Real Madrid, who would go on to become Barcelona’s fiercest rival, was founded in 1902.

As a testament to how the game had spread, the first World Cup was organized in 1930 and was held not in England, or even in Europe, but in Uruguay. The hosts knocked off Argentina in the final to capture the first-ever World Cup title. Italy became the first European World Cup winner and the first back-to-back winner, taking home the Cup in both 1934 and 1938.

Stars Are Born

As soccer gained popularity throughout the twentieth century, it attracted the world’s most gifted athletes. With televised matches becoming popular and increasing amounts of other media coverage to highlight their successes, stars and national heroes were born on the pitch. Just as Michael Jordan popularized the NBA in the 1980s and ‘90s, these men helped turn soccer into the beloved sport it is today.

Puskas Leads Hungary to International Glory

One of the game’s first stars to emerge was the Hungarian-born Ferenc Puskas. Puskas began his club career playing for his hometown Budapest Honved in 1943. A prolific striker, the hometown boy scored a remarkable 358 goals in his twelve-year tenure, which saw 350 appearances.

One of the game’s first stars to emerge was the Hungarian-born Ferenc Puskas. Puskas began his club career playing for his hometown Budapest Honved in 1943. A prolific striker, the hometown boy scored a remarkable 358 goals in his twelve-year tenure, which saw 350 appearances.

Puskas received little publicity playing in the humble Nemzeti Bajnoksag Hungarian League, despite leading Honved to five league titles. He made his name on the international pitch in the 1950s, ushering in a dominant era of Hungarian soccer. Early in the decade, Puskas led a Hungarian “Golden Team” to a 32-match unbeaten streak, an Olympic gold, and a World Cup second-place finish.

Scoring in quarterfinals, semis, and finals of Hungary’s 1952 Olympic gold effort, Puskas’ four goals helped prove to the world that the Hungarians could play this game at a high level. The success would continue into the 1954 World Cup, where Hungary was considered the favorite.

Scoring four goals in this tournament as well, Puskas helped play Hungary into the finals against West Germany. Puskas fractured his ankle in a group stage match versus these same Germans and would amazingly play in the finals’ rematch and even score a goal. In a controversy-riddled match dubbed “The Miracle of Bern,” the Germans narrowly defeated Hungary in comeback fashion 3-2.

In this match, Puskas had a second goal, a would-be late equalizer, nullified on a questionable offsides call. The defeat crushed Hungary’s spirit, and the nation has yet to return to a World Cup final.

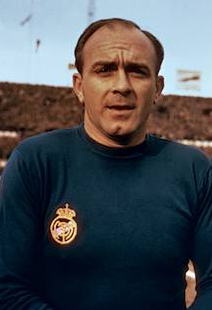

Di Stefano Becomes El Clasico Legend

While Puskas was tearing up the Hungarian league, the Argentinian native Alfredo Di Stefano was working his magic in Spain’s La Liga. Di Stefano was defined by this twelve-year tenure at Real Madrid, in which he scored 216 goals and lead his team to eight La Liga titles and five consecutive European Cups.

While Puskas was tearing up the Hungarian league, the Argentinian native Alfredo Di Stefano was working his magic in Spain’s La Liga. Di Stefano was defined by this twelve-year tenure at Real Madrid, in which he scored 216 goals and lead his team to eight La Liga titles and five consecutive European Cups.

Perennially the two best teams in La Liga, Real Madrid and Barcelona seem to vie for many major championships each year. This brewed quite a rivalry, which has become known simply as “El Clasico.” Performances in El Clasico matches would be weighted very heavily when evaluating a player’s worth. This is where Di Stefano shone.

Finding the back of the net eighteen times against Barca in his career, Di Stefano remains as Madrid’s leading all-time goal scorer in the rivalry. Amazingly, this is not even considered his greatest accomplishment on the pitch.

From 1956 to 1960, Di Stefano scored a goal in each of five straight European Cup finals, winning all five. The 1960 final, often considered the best display of talent in European Cup history, saw Real Madrid drub Eintracht Frankfurt 7-3. In this match, Di Stefano notched a hat trick, while his teammate Ferenc Puskas actually scored four times.

Easily one of Europe’s best teams in today’s game, Real Madrid was propelled into prominence by this spectacular run in the 1950s. After Di Stefano’s amazing success, Madrid became a coveted destination for the game’s top players. Real Madrid still holds the records for most La Liga titles and most European Cups.

Pele Propels Brazil to the Top

Brazil owns the current record for World Cup titles with five, but their dominance did not begin until a 17-year-old Pele dazzled at the 1958 World Cup. Pele’s hat trick in the semifinal versus France served as his announcement to the world that, although still a teenager, he was the greatest player to date. He then went on to score twice more in the final, ending the tournament with six goals and a World Cup title.

Brazil owns the current record for World Cup titles with five, but their dominance did not begin until a 17-year-old Pele dazzled at the 1958 World Cup. Pele’s hat trick in the semifinal versus France served as his announcement to the world that, although still a teenager, he was the greatest player to date. He then went on to score twice more in the final, ending the tournament with six goals and a World Cup title.

Pele then looked equally as impressive in the 1959 South American Championship, scoring eight goals. It is no wonder that Pele entered the 1962 World Cup as the consensus greatest player on Earth. Injuries limited his playing time, but the Brazilians still managed to win the title, their second straight.

In one last hoorah, Pele decided to play in the 1970 World Cup after initially announcing he was retiring from the event. His efforts were invaluable toward winning Brazil its third World Cup title. This year’s Cup was the first to be broadcast in color, and viewers were reportedly captivated by Brazil’s bright yellow shirts, and of course, the terrific play of Pele. This impression has led many to cheer for Brazil to this day.

The 1970 final between Brazil and Italy saw one of the greatest World Cup final performances from Pele, scoring once and assisting twice in a 4-1 winning effort. Pele went out on top, deciding to end his international career the following year. Brazil boasted a 67-11-14 record in Pele’s 92 matches.

Pele’s legendary status transcended soccer. He was a living god among his native Brazilians and soccer fans everywhere. He was named FIFA Player of the Twentieth Century and was also placed on TIME Magazine’s list of the 100 Most Influential People of the Twentieth Century.

Maradona Becomes a “D10S” Himself

As Pele’s career ended, another legend’s began. After witnessing two extraordinary decades out of Pele, no one predicted the sport’s next transcendent talent would emerge in the same decade. The Argentinian Diego Maradona played for his first club, Argentinos Juniors, in 1976. When he hung up his spikes in 1997, the world could not help but think they had witnessed the second coming of Pele.

As Pele’s career ended, another legend’s began. After witnessing two extraordinary decades out of Pele, no one predicted the sport’s next transcendent talent would emerge in the same decade. The Argentinian Diego Maradona played for his first club, Argentinos Juniors, in 1976. When he hung up his spikes in 1997, the world could not help but think they had witnessed the second coming of Pele.

Much like his Brazilian counterpart, Maradona was esteemed for his terrific international play. In 91 matches with the Argentinian national team, Maradona found the back of the net 34 times. In his 21 World Cup appearances, Maradona scored eight goals, while also being credited with eight assists.

Known as Golden Boy, Maradona cemented his position as the world’s best player in the 1986 World Cup in Mexico. With five goals and five assists, Maradona was involved in over half of his team’s shots. Opposing defenses resorted to physicality in an attempt to slow him down, fouling the 25-year-old a record 53 times over the course of the tournament.

In one of the greatest matches ever played, Maradona single-handedly led his Argentinians past the English in the quarterfinals, scoring two of the most memorable goals in history, the latter of which was voted FIFA’s Goal of the Twentieth Century.

On top of the 1986 World Cup title, Maradona also led his nation to the Artemio Franchi Trophy, a precursor to the Confederations Cup, in 1993. The Argentinians never surrounded Maradona with elite talent, so these championships illustrate just how talented and dominant he was. These efforts earned Maradona the nickname D10S, a play on the Spanish word for God and his jersey number ten.

Two decades prior, there was no question that Pele was the best soccer player of the twentieth century. After Maradona’s reign, however, FIFA concluded that he should be named co-Player of the Century along with Pele.

Messi Aims to Take the Throne

After debating for years whether Maradona was the best player in history, the debate is now whether Maradona is even the best player from Argentina. Bursting onto the scene in 2003, Lionel Messi has been nothing short of spectacular in his club play at Barcelona.

After debating for years whether Maradona was the best player in history, the debate is now whether Maradona is even the best player from Argentina. Bursting onto the scene in 2003, Lionel Messi has been nothing short of spectacular in his club play at Barcelona.

Messi has set the record for the most goals ever in El Clasico along with the records for most goals and assists ever in La Liga play. Most impressively, Messi tops the all-time list for goals in one European club season. He has been instrumental in Barcelona’s success in both the UEFA Champions League and the Copa Del Rey. No one disputes that Messi’s club career is the greatest in history, but his lack of results in international play has frustrated his fans.

Much of Messi’s story is yet to be written, as it is figured the Argentinian still has plenty of productive soccer left in him. His lack of a World Cup title keeps many from proclaiming him the best ever, but he entered the discussion at a very young age. Messi currently holds the record for the most Ballon d’Or awards, given to the world’s best player each year.

Soccer fans love their tournaments and championships. Currently, the World Cup is the most prestigious international competition. The UEFA Champions League in Europe, considered by some to contain better talent than the World Cup, is the most prestigious tournament for club teams.

Soccer is now gaining quite a following in the US. The sport is thriving, and many consider the late 2000s and the 2010s to be its golden years. The El Clasico rivalry is as strong as ever, while the World Cup is seeing much more parity.

Soccer is the world’s sport. Nothing else is remotely close to matching it.