Baseball Legends

How do you determine who the greatest baseball players of all time are? It’s a question that is very difficult to answer.

How do you determine who the greatest baseball players of all time are? It’s a question that is very difficult to answer.

Although baseball is a game of numbers, those numbers don’t always tell the entire story, especially when comparing players from different generations. Of all the main professional sports, baseball is the game which has changed the most dramatically over the years, forcing us to take a player’s era into account when measuring their greatness.

For example, it was much easier to put up big offensive numbers during the “lively ball era” of the 1920s and 1930s than it was during the “dead ball era” of the two decades prior to the ‘20s. As the nicknames of those two eras suggest, baseball switched the ball it was using, replacing a rubber-core ball with a cork-and-rubber ball that led to an extreme increase in batting averages and home run totals.

How do you compare players from the “steroid era” of the late 1990s (when baseball turned a blind eye to performance-enhancing drugs, capitalizing on interest generated by the pursuit of the single-season home run record) with players who didn’t use PEDs? And how do you compare players in the old days, when starting pitchers routinely went the full nine innings, to hitters in the modern generation that have to face 3-4 different hurlers per game?

As you can see, it’s impossible to do an apples-to-apples comparison of MLB’s greatest players. That’s why we’ve opted to come up with this list of baseball legends instead.

So what makes a baseball legend? That’s not an easy question to answer, either. Instead of relying purely on statistics, there’s a lot of subjectivity involved, and it’s difficult (if not impossible) to recognize all the worthy players while keeping the list at a manageable number.

But we’ve given it our best shot. Here are the 28 players that we feel most deserve the status of baseball legends, based on the numbers they put up during their careers, their place among their peers, and the legacies they left behind.

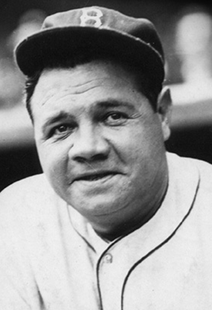

Babe Ruth

Not many players loom larger in the grand history of baseball than Babe Ruth, and we’re not referring to his girth (contrary to popular belief, the Bambino wasn’t really considered to be overweight until the final years of his career).

Not many players loom larger in the grand history of baseball than Babe Ruth, and we’re not referring to his girth (contrary to popular belief, the Bambino wasn’t really considered to be overweight until the final years of his career).

No, Ruth’s greatness has always transcended baseball because of his larger-than-life charisma, whether it was his fun-loving nature off the field or his flair for the dramatic on it. One of the first in the sport to swing from the heels with the main intent of hitting home runs, Ruth was a fan favorite throughout the 1910s and 1920s because of his immense power. He led the American League in home runs 12 times, and his 714 career dingers was an MLB record that stood for more than 40 years.

Before Ruth became the Sultan of Swat, he was also a dominant pitcher as a lefthander for the Boston Red Sox. With Ruth anchoring the staff, Boston won three World Series titles in a five-year span. However, financial hardships forced the Red Sox to sell Ruth’s rights to the Yankees in 1919, and he hit 54 homers the following season as a full-time outfielder for the Bronx Bombers. And while Ruth went on to win four more World Series crowns with the Yankees, Boston didn’t win the MLB title again for 85 years, a drought that became known as “The Curse of the Bambino.”

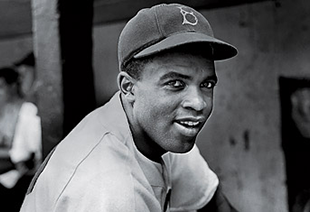

Jackie Robinson

When no one else in your sport is ever allowed to wear your number again, you know you’ve reached legendary status.

When no one else in your sport is ever allowed to wear your number again, you know you’ve reached legendary status.

That is the honor that was bestowed upon Jackie Robinson and his #42 in 1997, and with good reason. Robinson bravely put an end to racial segregation in professional baseball when he suited up for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, becoming the first black man to play in a Major League Baseball contest.

Although Robinson is best remembered for breaking MLB’s color barrier, he was a heck of a player as well. He won the first-ever MLB rookie-of-the-year award in 1947, earned six consecutive All-Star nominations, and was named the National League MVP in 1949. Robinson and the Dodgers went to six World Series during his 10-year career, winning it all in 1955.

Robinson passed away in 1972 at the age of 53, but his memory lives on. Every year on April 15, MLB commemorates the anniversary of his breaking of the color barrier by having every player wear #42 on their uniform backs.

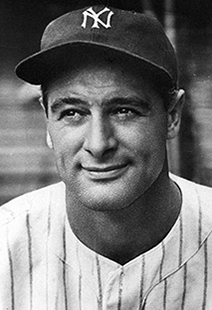

Lou Gehrig

Like Jackie Robinson, Lou Gehrig is mostly remembered for achieving one of MLB’s most significant milestones, playing in an incredible 2,130 consecutive games throughout the 1920s and ’30s. Gehrig’s streak stood as the longest in MLB for nearly 60 years, when it was finally surpassed by Cal Ripken Jr., and no other player has come within 800 games of it.

Like Jackie Robinson, Lou Gehrig is mostly remembered for achieving one of MLB’s most significant milestones, playing in an incredible 2,130 consecutive games throughout the 1920s and ’30s. Gehrig’s streak stood as the longest in MLB for nearly 60 years, when it was finally surpassed by Cal Ripken Jr., and no other player has come within 800 games of it.

Nicknamed the “Iron Horse” because of his durability, Gehrig’s greatness as a ballplayer is often overlooked. He remains one of a handful of players to win the batting Triple Crown (lead the league in batting average, home runs, and stolen bases), won six World Series titles with the Yankees, and was a two-time American League MVP. Over his 17-year career, Gehrig hit .340 with nearly 500 home runs and 2,000 RBI, including 23 grand slams.

In a sad twist of irony, Gehrig’s streak was ended by his battle with a neuromuscular illness that is now known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. Two years after he voluntarily pulled himself out of the Yankees lineup due to the disease, Gehrig died from the illness at the age of 37.

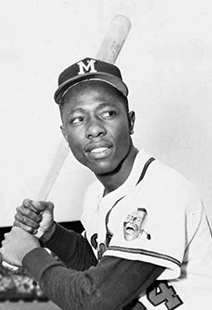

Hank Aaron

Hank Aaron is one of the greatest power hitters that baseball has ever seen. His 755 career home runs eclipsed the previous MLB record set by the iconic Babe Ruth, and Aaron remains MLB’s all-time leader in runs batted in (2,297), total bases (6,856), and extra-base hits (1,477).

Hank Aaron is one of the greatest power hitters that baseball has ever seen. His 755 career home runs eclipsed the previous MLB record set by the iconic Babe Ruth, and Aaron remains MLB’s all-time leader in runs batted in (2,297), total bases (6,856), and extra-base hits (1,477).

Hammerin’ Hank reached those meteoric numbers through incredible consistency. He hit at least 24 home runs in 19 consecutive seasons, reaching the 30-homer plateau in 15 of those years. Perhaps the most telling sign of his sustained excellence is that he was named an MLB All-Star on a record 25 occasions.

Aaron’s reign as MLB home run king ended in 2009 when he was surpassed by Barry Bonds. Although Bonds was believed to have used steroids in order to achieve his home run numbers, Aaron showed tremendous class by congratulating Bonds through a video message that was displayed on the scoreboard after Bonds broke his record. It was the same class, dignity, and humility that Aaron displayed during his pursuit of Ruth’s home run record, when Aaron received countless racist letters and even death threats.

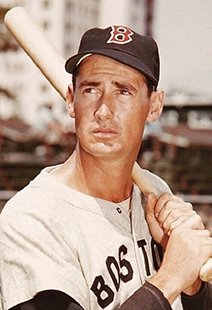

Ted Williams

There may not have been a greater pure hitter in Major League Baseball history than Ted Williams.

There may not have been a greater pure hitter in Major League Baseball history than Ted Williams.

Known as the “Splendid Splinter,” “Teddy Ballgame,” or simply “The Kid,” Williams hit .344 during a 19-year career spent entirely with the Boston Red Sox. Though he was a six-time American League batting average champion, Williams also put up solid power numbers, topping the AL four times in both home runs and runs batted in. In 1942 and 1947, he led the league in all three offensive categories, making him the last two-time winner of the Triple Crown. Williams is also the last hitter to finish a season with a batting average higher than .400, hitting at a .406 clip in 1941. (Rather than sit out the final two games of the season in order to preserve his .400 average, Williams collected six hits in a season-ending doubleheader to finish well above .400.)

Despite all of his individual success with the Red Sox, Williams never managed to endear himself to Boston fans during his playing career. Part of that may have been due to Boston’s inability to win a World Series with Williams, and part may have been due to his ornery personality (he never tipped his hat to the crowd as a player). However, Williams and the BoSox fans resolved their differences after his retirement, highlighted by a moving ceremony prior to the 1999 MLB All-Star Game at Fenway Park. It was a perfect final public appearance for Williams, who passed away three years later at the age of 83.

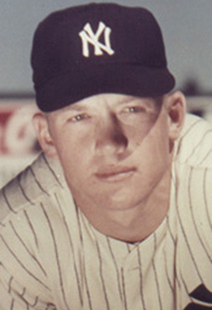

Mickey Mantle

It’s hard to believe that one of the greatest ball players of all time nearly retired from the sport as a rookie, but that’s exactly what Mickey Mantle came close to doing in 1951. After struggling in his first games as the Yankees’ right fielder and being sent to the minor leagues, Mantle called his father to tell him he was considering quitting the game.

It’s hard to believe that one of the greatest ball players of all time nearly retired from the sport as a rookie, but that’s exactly what Mickey Mantle came close to doing in 1951. After struggling in his first games as the Yankees’ right fielder and being sent to the minor leagues, Mantle called his father to tell him he was considering quitting the game.

If it weren’t for that sobering conversation with his dad (who suggested Mantle come back to his native Oklahoma and work in the mines), MLB might have been robbed of one of the greatest all-around talents to play the sport. Whether it was hitting, fielding, or running the bases, Mantle did it all – including hitting for tremendous power from both sides of the plate. In fact, many consider Mantle to be the best switch-hitter of all time.

Mantle played his entire 18-year career with the Yankees, first as a center fielder and then at first base. During that span, he helped New York to seven World Series titles and 12 American League pennants, was named AL MVP on three occasions, hit .300 ten times, and was a four-time AL home run champion. Mantle is also the last player to lead all of baseball in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in, claiming the Triple Crown in 1956 with a .353 average, 52 bombs, and 130 RBI.

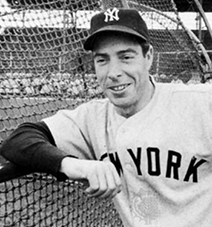

Joe DiMaggio

In a way, it’s a shame that we best remember Joe DiMaggio for his 56-game hitting streak and for once being married to Marilyn Monroe.

In a way, it’s a shame that we best remember Joe DiMaggio for his 56-game hitting streak and for once being married to Marilyn Monroe.

That’s not to diminish DiMaggio’s amazing streak (the only player to even reach 40 straight games since then was Pete Rose, who hit safely in 44 consecutive games in 1978) or his celebrity status (he’s referenced in numerous famous songs, including Simon & Garfunkel’s classic Mrs. Robinson). But when you focus on those achievements, you might not fully appreciate everything else that DiMaggio accomplished in his brilliant but shortened career.

How great was the Yankee Clipper? Well, despite missing three years of his prime because he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II, DiMaggio still won nine World Series championships and 10 American League pennants during his 13 seasons with the New York Yankees. He hit .325 during his career, driving in more than 1,500 runs and ranking fifth all-time in homers at the time of his retirement.

By the way, that 56-game hitting streak in 1941 wasn’t even the longest streak in DiMaggio’s professional baseball career! He hit safely in 61 consecutive games during his rookie season with the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League, four years before he joined the Yankees.

Ty Cobb

Many of baseball’s early records in hitting and base-running categories were set in the 1920s and 1930s by Ty Cobb, including several standards that still stand nearly a century later.

Many of baseball’s early records in hitting and base-running categories were set in the 1920s and 1930s by Ty Cobb, including several standards that still stand nearly a century later.

Records that the Georgia Peach held for half a century included most career hits (4,191), runs scored (2,246), and stolen bases in a season (96). Although Pete Rose broke Cobb’s hits record in 1985 and Rickey Henderson eclipsed Cobb for the runs and stolen base marks, Cobb still owns Major League records for career batting average (.367), batting titles (12), and successful steals of home (54).

Cobb may have been more revered had it not been for his controversial life off the field, which included multiple allegations of racist behavior and assaults. However, those incidents were also reflective of the extreme intensity with which Cobb played the game, the very character trait that helped make him an all-time great.

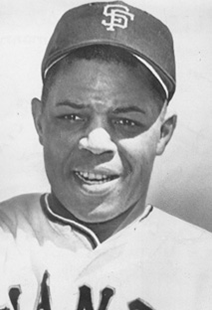

Willie Mays

Based on his defensive abilities alone, Willie Mays deserves inclusion on any list of baseball legends. Not only did the perennial Gold Glove-winning center fielder provide what is widely considered to be the greatest catch of all time, but he did it in the World Series to boot!

Based on his defensive abilities alone, Willie Mays deserves inclusion on any list of baseball legends. Not only did the perennial Gold Glove-winning center fielder provide what is widely considered to be the greatest catch of all time, but he did it in the World Series to boot!

With his New York Giants tied 2-2 with the powerful Cleveland Indians in the opening game of the 1954 World Series, Mays tracked down a 420-foot drive off the bat of Vic Wertz with an over-the-shoulder catch, making the grab with his back to home plate. The play, still known to this day simply as “The Catch,” came with two runners on in the eighth inning, saving the game for the Giants and enabling them to eventually prevail in extra innings.

But as good as he was defensively, Mays may have been even better with his bat. He is one of only five players in National League history to record 100 RBI in eight straight seasons, and his 660 career home runs ranks fifth all-time. Throw in his skills as a base-runner (Mays led the NL in stolen bases four straight years from 1956-59), his .304 lifetime batting average, and 24 All-Star Game appearances, and we’re clearly talking about one of the best players to ever take the diamond.

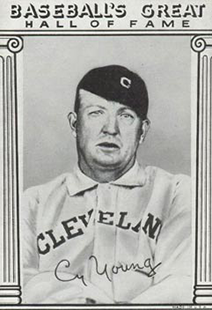

Cy Young

Due to the awards that are named in his memory, Cy Young’s name has become synonymous with elite pitching. Each season, the top hurler in both the American League and National League is recognized with the Cy Young Award, an honor that has been in place for more than 60 years.

Due to the awards that are named in his memory, Cy Young’s name has become synonymous with elite pitching. Each season, the top hurler in both the American League and National League is recognized with the Cy Young Award, an honor that has been in place for more than 60 years.

Young may have not been the most dominant pitcher in MLB history (in addition to owning the most victories ever with 511, he also suffered the most losses), but he was incredibly durable. Pitching in an era when there was no five-man rotation and when hurlers were expected to go the entire game, Young set records that will never be broken for innings pitched (7,356), starts (815), and complete games (749).

Another thing that set Young apart from his peers was how he “pitched,” rather than simply throwing the ball as fast as he could. All of those pitches over the years took a toll on his arm and caused his velocity to decline, but Young continued to thrive as a control specialist who led the league 14 times in fewest walks per nine innings.

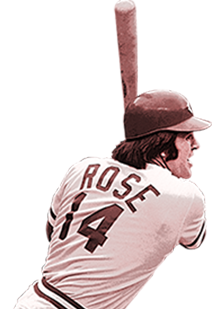

Pete Rose

You won’t find Pete Rose’s name in the Baseball Hall of Fame, but that’s no fault of his performance on the field. In fact, Rose tops baseball’s all-time list in several hitting categories, most notably the most hits (4,256) ever recorded in Major League play.

You won’t find Pete Rose’s name in the Baseball Hall of Fame, but that’s no fault of his performance on the field. In fact, Rose tops baseball’s all-time list in several hitting categories, most notably the most hits (4,256) ever recorded in Major League play.

Rose was the key cog in Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine of the 1970s, leading the Reds to three championships in a six-year span. In addition to his offensive prowess, Rose was a versatile defender (he’s the only player in MLB history to play more than 500 games at five different positions) and played with a fiery intensity that earned him the nickname “Charlie Hustle” before he’d even played a game in the Big Leagues. Rose wanted to win every game so badly that he even steamrolled over Indians catcher Ray Fosse to score the winning run in the 1970 All-Star Game, breaking Fosse’s shoulder in the process.

So why isn’t Rose in the Baseball Hall of Fame? Because he gambled on baseball during his career, including games involving his own team. Rose was banned from Major League Baseball in 1989 due to gambling accusations that he first denied, then finally admitted to 15 years later. But now that American society is more accepting of gambling than it used to be (including the 2018 Supreme Court decision to legalize sports betting in all states), it’ll be interesting to see if MLB is ever willing to forgive Rose for his past indiscretions and give him the Hall of Fame recognition that his on-the-field performance deserves.

Nolan Ryan

No pitcher in Major League Baseball history struck out as many opposing hitters as Nolan Ryan, who rung up 5,714 batters during his career – nearly a thousand more than any other pitcher to ever play the game.

No pitcher in Major League Baseball history struck out as many opposing hitters as Nolan Ryan, who rung up 5,714 batters during his career – nearly a thousand more than any other pitcher to ever play the game.

Though amassing those numbers would not have been possible had it not been for longevity in the sport (Ryan’s 27-year career is the longest in MLB history), the former fireballer didn’t just stick around in the game to pad his stats. Ryan was virtually as effective in his mid-40s as he was in his early 20s, exceeding 100 miles per hour on his fastball and also throwing a fast, hard-breaking curve.

When Ryan was on his game, he was literally unhittable. His seven career no-hitters are three more than any other pitcher in history, and his last no-no in 1991 came nearly 18 full years after his first one. The Ryan Express is also tied for the most one-hitters in baseball history (12) and added 18 career two-hitters, and he’s the all-time leader in fewest hits allowed per 9 innings pitched (6.56).

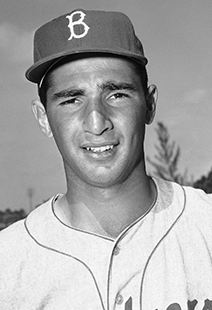

Sandy Koufax

Sandy Koufax struggled with control issues during the first six seasons of his MLB career, and arthritis in his throwing elbow forced him to retire prematurely at the tender age of 30. But for the seasons in between, the pitching numbers put up by the Dodgers left-hander might have been the best six-year stretch that baseball has ever seen.

Sandy Koufax struggled with control issues during the first six seasons of his MLB career, and arthritis in his throwing elbow forced him to retire prematurely at the tender age of 30. But for the seasons in between, the pitching numbers put up by the Dodgers left-hander might have been the best six-year stretch that baseball has ever seen.

After going just 36-40 in his first six campaigns, Koufax actually considered quitting baseball and focusing on his electronics business instead. But an increased dedication to fitness and some tweaks to his wind-up led to a breakthrough season in 1961, when Koufax led the league in strikeouts and made his first All-Star Game appearance. His following five seasons were even better, as Koufax led the National League in earned run average each year, also topping the Senior Circuit in wins and strikeouts on three occasions and winning the Cy Young Award in 1963, 1965, and 1966.

Despite the mediocre start to his career, Koufax owns the highest career winning percentage (.655) of any National League pitcher to throw more than 2,000 innings. If only his career hadn’t been cut short due to injury, those numbers would have undoubtedly been even better.

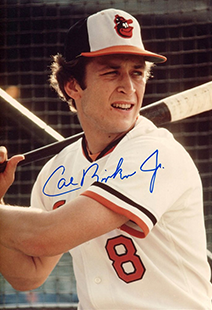

Cal Ripken Jr.

If Major League Baseball were to ever borrow a page from the National Basketball Association and base its logo on one specific player, Cal Ripken Jr. would be a leading candidate to be MLB’s version of Jerry West.

If Major League Baseball were to ever borrow a page from the National Basketball Association and base its logo on one specific player, Cal Ripken Jr. would be a leading candidate to be MLB’s version of Jerry West.

There was literally nothing could keep Ripken off the field from 1982-98, a 17-year stretch in which the Orioles shortstop started every single one of his team’s 2,632 games. That consecutive games streak was 500 games longer than the previous standard held by the “Iron Horse,” Lou Gehrig, and no other player in MLB history has even strung together half the number of consecutive games that Ripken did.

In addition to being baseball’s model for consistency and durability, Ripken also revolutionized the shortstop position as a larger man who hit for tremendous power. His 345 homers as a shortstop are an MLB record for the position (both Ernie Banks and Alex Rodriguez hit many of their home runs after changing positions), and his 3,184 hits are third-most among shortstops in history. Ripken also displayed humility and class throughout his career and even into retirement, where he continues to be one of baseball’s top ambassadors.

Shoeless Joe Jackson

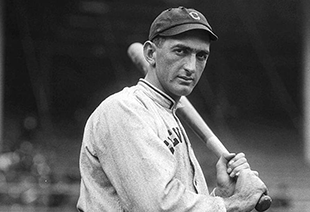

Hits were a bit easier to come by in the early days of baseball, when the pitching wasn’t as good, and the defense wasn’t, either. But while you need to take that into account when looking at the numbers compiled by Shoeless Joe Jackson from 1908-20, his .356 lifetime average is still the third-highest in baseball history.

Hits were a bit easier to come by in the early days of baseball, when the pitching wasn’t as good, and the defense wasn’t, either. But while you need to take that into account when looking at the numbers compiled by Shoeless Joe Jackson from 1908-20, his .356 lifetime average is still the third-highest in baseball history.

Jackson’s status as a baseball legend, however, is primarily due to his alleged involvement in the “Black Sox Scandal” of 1919, when several members of the Chicago White Sox were accused of intentionally losing the World Series. If Jackson was playing that World Series to lose, it was impossible to tell. His 12 hits in the Fall Classic against Cincinnati was the most in a World Series until 1964, he didn’t make any errors, and he even threw out a runner at the plate. But despite Jackson’s insistence that he had nothing to do with the conspiracy to throw the series, he was one of eight players banned for life by then-MLB commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

The possibility that Jackson was unfairly robbed of his baseball career has been hotly debated over the years. His sad story has been referenced in several prominent movies, including Eight Men Out (a movie about the Black Sox Scandal) and Field of Dreams (when an Iowa farmer builds a baseball field so Jackson can play the game again). And in 2015, the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum unsuccessfully appealed to MLB commissioner Rob Manfred for Jackson’s reinstatement, which would allow him to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Rickey Henderson

No one in the history of baseball was better at manufacturing a run for his team than Rickey Henderson was throughout the 1980s and ’90s.

No one in the history of baseball was better at manufacturing a run for his team than Rickey Henderson was throughout the 1980s and ’90s.

Once Henderson safely reached first base, it was a near-certainty that he’d soon be on second. The left fielder’s 1,406 career stolen bases are nearly 500 more than any other player in history, his 130 stolen bases in 1982 are also an MLB record, he’s the only player in American League history to steal 100 bases in a season (accomplishing the feat three times), and he ranked among baseball’s top 10 base stealers in 21 of his 25 seasons.

Henderson also specialized in reaching base safely, drawing the most “unintentional” walks in baseball history (Barry Bonds drew so many intentional walks during his prime that he’s the all-time leader in base on balls) in addition to his career .279 batting average. Combine Henderson’s running ability with his knack for getting on base, and it’s no wonder that he also holds MLB’s all-time record for career runs scored.

Barry Bonds

The career of Barry Bonds is one of the most controversial in baseball history. But even before the left fielder allegedly used steroids to help him become MLB’s all-time home run king, he may have already been the greatest all-around player of his generation.

The career of Barry Bonds is one of the most controversial in baseball history. But even before the left fielder allegedly used steroids to help him become MLB’s all-time home run king, he may have already been the greatest all-around player of his generation.

The godson of Willie Mays, Bonds was named National League MVP in both 1990 and 1992 while finishing second in voting the season in between, leading the Pittsburgh Pirates to a couple of playoff appearances. Although Bonds averaged more than 20 homers in his first seven MLB seasons with Pittsburgh, he was better known for hitting for average, hitting tons of doubles, stealing bases (including a career-high 52 in 1990), and playing excellent defense.

After leaving Pittsburgh to sign a lucrative free-agent contract with the San Francisco Giants, Bonds continued to put up stellar overall numbers, earning another MVP award in 1993. However, baseball fans were more interested in Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa’s pursuit of Roger Maris’s single-season home run record in the late 1990s, which is believed to have made Bonds jealous and led to his alleged steroid use. From that point, Bonds went on a home-run-hitting rampage, hitting a record 73 bombs in 2001 and averaging nearly 60 round-trippers per season from 2000-04.

In August of 2007, Bonds hit his 756th home run to surpass Hank Aaron for the most in MLB history. He retired one month later with 762 career blasts, seven National League MVP awards, the all-time record for on-base percentage… and a tarnished legacy. Although Bonds continues to insist that he never took steroids, he was not elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first six years of eligibility, and many believe he never will.

Ichiro Suzuki

If he hadn’t spent the first nine years of his professional career playing in Japan, Ichiro Suzuki might have been Major League Baseball’s all-time hits leader. Over the span of his 27-year career, Ichiro collected more than 4,300 hits, a number that would have surpassed Pete Rose for the most ever in MLB history.

If he hadn’t spent the first nine years of his professional career playing in Japan, Ichiro Suzuki might have been Major League Baseball’s all-time hits leader. Over the span of his 27-year career, Ichiro collected more than 4,300 hits, a number that would have surpassed Pete Rose for the most ever in MLB history.

When Ichiro came to North America in 2001 as a 28-year-old, he immediately took MLB by storm. Despite receiving intense media coverage as the greatest baseball talent to ever come out of Japan, Ichiro recorded 242 hits in his first season with the Seattle Mariners, winning the American League batting title, stolen bases crown, rookie-of-the-year award, and MVP. Three years later, Ichiro broke the single-season hits record that had stood for the previous 84 years, collecting 262 base knocks.

Ichiro posted 10 consecutive 200-hit seasons with the Mariners (leading the American League in hits each of those years) before being traded to the Yankees in 2012, when he was 38. After short stints in New York and Miami, he fittingly returned to Seattle in 2018 to finish his brilliant career.

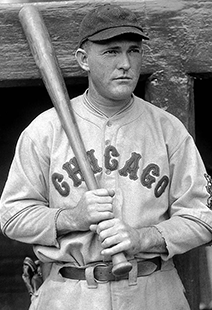

Ernie Banks

When Ernie Banks began blasting home runs as a shortstop for the Chicago Cubs in the late 1950s, it was something that baseball had never seen from the middle infield position.

When Ernie Banks began blasting home runs as a shortstop for the Chicago Cubs in the late 1950s, it was something that baseball had never seen from the middle infield position.

Banks’ five consecutive 40-homer seasons with Chicago (including a pair of years in which he led the National League in round-trippers) were the five highest single-season totals by a shortstop for more than 40 years, when Alex Rodriguez began posting 50-homer years with the Texas Rangers.

Known affectionately as “Mr. Cub,” Banks drove in more than 1,600 runs, was a 14-time All-Star, and won two National League MVP awards during his 18-year career in Chicago, the latter years of which were spent at first base. Although Banks wasn’t able to snap the Cubbies’ lengthy World Series drought that eventually extended to 108 years, he was the franchise’s first player to have his number retired. He was also a legend in the Chicago area after his retirement, founding a charity and running for political office.

Following his death in 2015, the Cubs featured Banks’ #14 on the field behind home plate for the entire season, the type of honor reserved for only the greatest of legends.

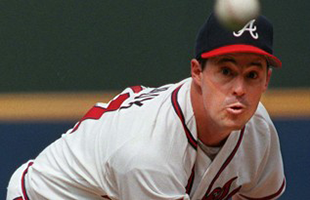

Greg Maddux

Weighing 170 pounds and with a fastball that topped out in the low 90s, Greg Maddux wasn’t the most intimidating of mound presences. Not until hitters stepped into the batter’s box, at least, where the greatest of sluggers were routinely brought to their knees by Maddux’s incomparable repertoire of cunning and precision.

Weighing 170 pounds and with a fastball that topped out in the low 90s, Greg Maddux wasn’t the most intimidating of mound presences. Not until hitters stepped into the batter’s box, at least, where the greatest of sluggers were routinely brought to their knees by Maddux’s incomparable repertoire of cunning and precision.

Maddux’s calling card was his pinpoint accuracy. Not only was he a nine-time leader of the National League in fewest walks per 9 innings, but he also controlled the ball within the strike zone, routinely inducing groundballs with low pitches on the outside corner of the plate.

Although Maddux’s career ERA doesn’t even crack the top 200 of all-time pitchers, those numbers were inflated towards the end of his career as he pitched until the age of 42. During the 1990s and early 2000s, he was a huge reason why the Atlanta Braves made the playoffs in a record 14 straight seasons. Maddux captured four consecutive Cy Young Awards from 1992-95, finished in the top five of voting in four of the next five seasons, and posted an ERA of 3.00 or lower in every year but one from 1992-2000.

Alex Rodriguez

Though massive contracts, admitted steroid use, and playoff struggles made Alex Rodriguez a polarizing figure throughout his career, there’s no questioning his legacy as the greatest power-hitting infielder in the history of the game.

Though massive contracts, admitted steroid use, and playoff struggles made Alex Rodriguez a polarizing figure throughout his career, there’s no questioning his legacy as the greatest power-hitting infielder in the history of the game.

Billed as a prodigious talent when he first broke into the big leagues with the Seattle Mariners in 1994, it didn’t take A-Rod long to live up to the hype. Two years later and at the age of 20, Rodriguez led the American League in batting average (.358), runs (141), and doubles (54), adding 36 homers and 123 runs batted in en route to finishing second in the MVP race. And in 1998, Rodriguez became just the third player in MLB history to reach 40 homers and 40 stolen bases in the same season.

When you consider all that Rodriguez accomplished early in his career (he had already hit 184 home runs before he was 25 years old), it’s puzzling why he even risked tarnishing his career by turning to performance-enhancing drugs. Maybe it was to deal with the chronic pain in his hip, or perhaps it was to live up to the pressure of signing the biggest free-agent contract in MLB history in 2001 (Rodriguez averaged more than 50 home runs over his first three seasons with the Texas Rangers). But even though Rodriguez would eventually finish his career with the fourth-most homers in baseball history (696), he’ll forever be tainted by the decision to take steroids, a decision for which he referred to himself as a “jackass” following his retirement.

Derek Jeter

The statistical accomplishments of Derek Jeter are enough to earn him a place among the all-time MLB legends. The long-time Yankees shortstop ranks sixth in baseball history in hits (3,465), 11th in runs (1,923), 10th in shortstop assists (6,605), and 12th in times on base, and his career .311 batting average is among the best in the modern era.

The statistical accomplishments of Derek Jeter are enough to earn him a place among the all-time MLB legends. The long-time Yankees shortstop ranks sixth in baseball history in hits (3,465), 11th in runs (1,923), 10th in shortstop assists (6,605), and 12th in times on base, and his career .311 batting average is among the best in the modern era.

But Jeter’s lasting legacy will be more about how he consistently came up big when the stakes were at their highest. Whether it was diving into the stands to make incredible catches, hitting important home runs, or singling up the middle in his final career at-bat at Yankee Stadium, Jeter seemingly always delivered in the most dramatic of moments. He was simply a winner, evidenced by the fact that the Yankees never finished below .500 in any of Jeter’s 20 MLB seasons.

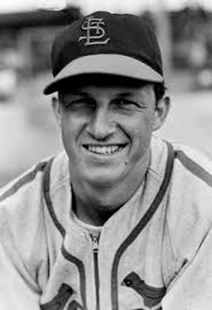

Stan Musial

Had it not been for an injury that damaged Stan Musial’s throwing shoulder as a teenage prospect, baseball might have been deprived of one of the greatest outfielders in history.

Had it not been for an injury that damaged Stan Musial’s throwing shoulder as a teenage prospect, baseball might have been deprived of one of the greatest outfielders in history.

Yes, Musial was initially a left-handed pitcher when the St. Louis Cardinals signed him to a minor-league contract in 1938. But after Musial badly injured his left shoulder diving for a ball, the Cardinals chose instead to put him in the outfield. As a full-time hitter, Musial quickly took off, hitting .426 in limited action as a rookie in 1941 and then raking at a .315 clip in his first full big-league season.

At the age of 22, Musial led the National League in games, plate appearances, hits, doubles, home runs, batting average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and total bases en route to claiming the NL MVP. He’d go on to hit .310 or better in 16 more consecutive seasons, and he retired as the NL’s all-time leader in hits, runs scored, and total bases, helping the Cardinals to three World Series championships in the process.

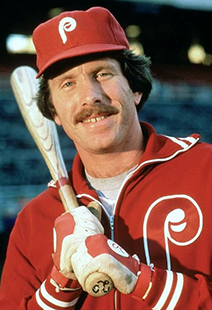

Mike Schmidt

Mike Schmidt was one of the most feared power hitters in baseball throughout the 1970s and ‘80s. He topped the National League in home runs eight times, including 1980 when his 48 blasts set a new MLB record for homers by a third baseman. Schmidt also led the NL in runs batted in four times, won three MVP awards, and led the Phillies to the 1980 World Series title.

Mike Schmidt was one of the most feared power hitters in baseball throughout the 1970s and ‘80s. He topped the National League in home runs eight times, including 1980 when his 48 blasts set a new MLB record for homers by a third baseman. Schmidt also led the NL in runs batted in four times, won three MVP awards, and led the Phillies to the 1980 World Series title.

As great as he was with the bat, Schmidt was also an elite defender. He essentially owned the NL Gold Glove Award from 1976-84, winning it nine consecutive seasons, and added his 10th career Gold Glove in 1986. An All-Star in 16 of his 18 career seasons, Schmidt is considered by many to be the best third baseman in MLB history.

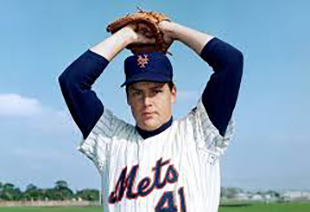

Tom Seaver

Tom Seaver nearly single-handedly transformed the New York Mets from a laughingstock into a World Series contender when he joined the team in 1967. After averaging more than 110 losses per year in the five seasons before Seaver’s arrival, New York won the World Series in his third year with the team, then returned to the Fall Classic once again four years later.

Tom Seaver nearly single-handedly transformed the New York Mets from a laughingstock into a World Series contender when he joined the team in 1967. After averaging more than 110 losses per year in the five seasons before Seaver’s arrival, New York won the World Series in his third year with the team, then returned to the Fall Classic once again four years later.

Fittingly known as “The Franchise,” Seaver was considered the best pitcher in baseball during his 10 years with the Mets. He claimed three Cy Young Awards, won 20 games five times (including 25 in 1969), led the league in strikeouts five times, and was a three-time NL champion in both wins and ERA.

After retiring in 1986 with 311 career victories, 3,640 strikeouts, 61 shutouts, and a 2.86 ERA, Seaver was inducted into the Hall of Fame six years later with a then-record 98.84% of votes.

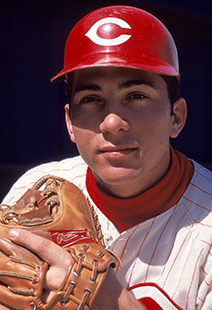

Johnny Bench

Johnny Bench is considered the benchmark by which the greatest catchers are measured, and the numbers back it up.

Johnny Bench is considered the benchmark by which the greatest catchers are measured, and the numbers back it up.

Offensively, few backstops have been better than Bench was from 1967-83 for the Cincinnati Reds. He collected more than 2,000 hits, scored nearly 1,100 runs, hit close to 400 home runs, and drove in approximately 1,400 runs during that span for the Reds, earning the NL rookie-of-the-year award in 1968 and claiming MVP honors in 1970 and 1972.

Bench’s value behind the plate was also tremendous. He threw out an incredible 57.2% of would-be base stealers in his rookie season, when he won the first of 10 consecutive Gold Glove Awards. Meanwhile, his career WAR (wins above replacement, which factors for both offensive and defensive abilities) of 75 is the highest of any catcher to ever play the game. With Bench leading the way, the Big Red Machine won back-to-back World Series in 1975-76 and claimed two other NL pennants during the ’70s as well.

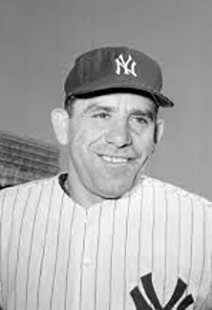

Yogi Berra

Though he’s known more for his eccentric personality and quirky sayings (“It ain’t over ‘til it’s over” and “90% of this game is half mental” are two of the beauties attributed to him), Yogi Berra was one heck of a catcher as well.

Though he’s known more for his eccentric personality and quirky sayings (“It ain’t over ‘til it’s over” and “90% of this game is half mental” are two of the beauties attributed to him), Yogi Berra was one heck of a catcher as well.

Named American League MVP in 1951, 1954, and 1955, Berra hit .285 in his 19-year career while swatting 358 home runs, driving in 1,430 runs, and even legging out 49 triples. He also did a whole lot of winning, claiming an MLB-record 10 World Series championships with the Yankees from 1946-63 and going to the Fall Classic 14 times in that 18-year span.

Rogers Hornsby

Rogers Hornsby’s place as the best right-handed hitter in MLB history didn’t come by coincidence.

Rogers Hornsby’s place as the best right-handed hitter in MLB history didn’t come by coincidence.

After hitting just .246 as a rookie in 1915, Hornsby worked at a farm during the winter to put on 30 pounds of muscle. When he returned the following season, he hit the first pitch he saw for a triple, setting the tone for a 10-year run in which Hornsby won the National League batting title seven times.

Hornsby’s dedication to baseball was evident throughout his career, to the point that he wouldn’t even attend movie theaters because he feared they would strain his eyes. All of that dedication paid off with a career batting average of .358 (the highest of any right-handed hitter to play the game, and behind only Ty Cobb for the all-time lead), two MVP awards, four NL RBI titles, and a pair of Triple Crowns. Hornsby also owns the record for the highest batting average in a single season, hitting .424 in 1924.